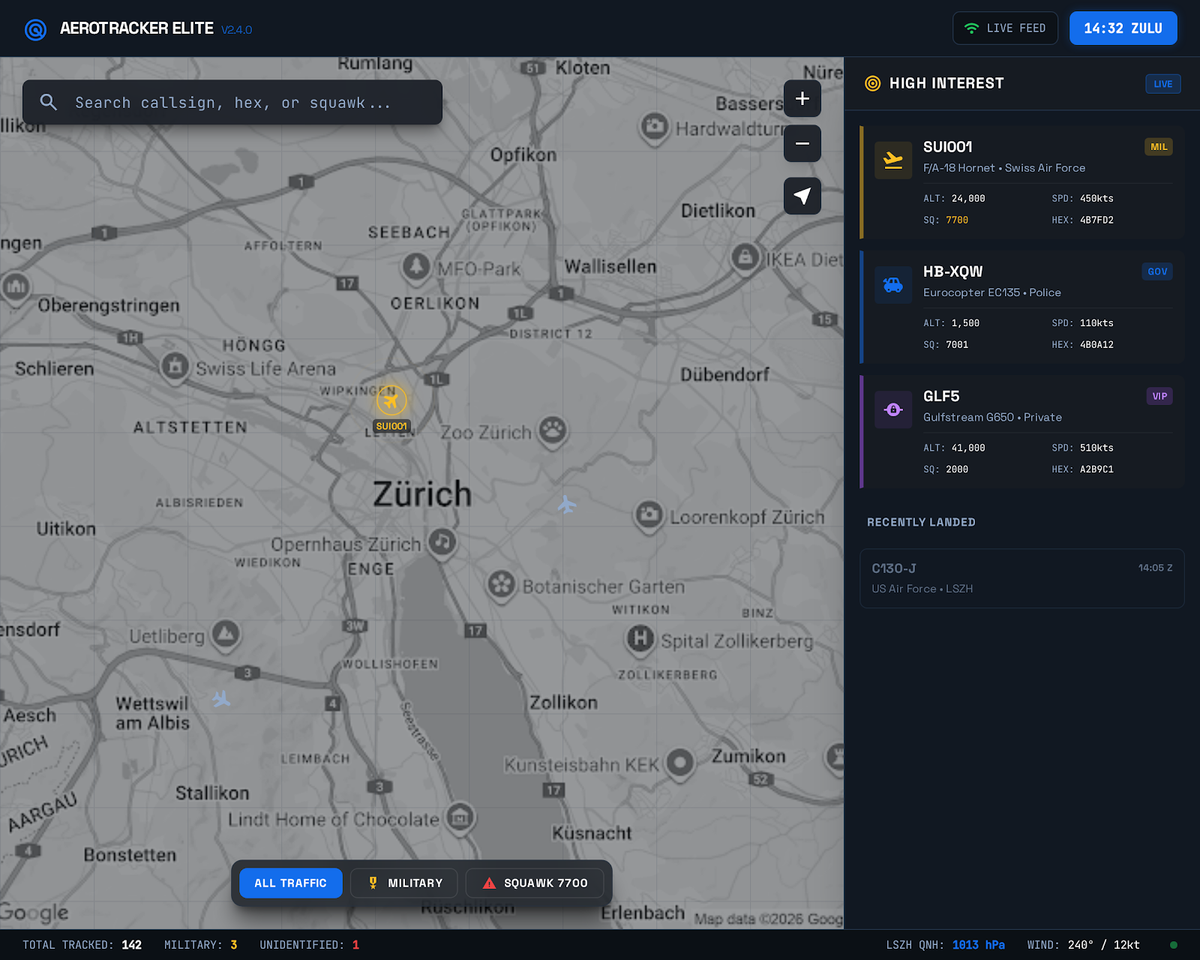

ADS-B rare aircraft tracker

Many tactical aircraft either suppress ADS-B entirely, use it sporadically, or fly with blocked tail numbers. Near a busy international hub you still catch plenty via Mode S, all-calls replies give you the ICAO address even without position.

This post is a follow-up to my original project: Tracking Planes with Raspberry Pi and ADS-B. If you haven't read that one yet, start there for the basics.

A note on legality: Receiving ADS-B signals is entirely legal. ADS-B operates on 1090 MHz as an unencrypted broadcast protocol—aircraft intentionally transmit their positions for aviation safety. Passive reception (no transmission) falls under the same category as listening to FM radio. Services like FlightRadar24 and ADS-B Exchange run commercial operations on this data. Military operators know their transmissions can be received, which is exactly why sensitive operations suppress ADS-B or use limited transponder modes.

Building a personal aircraft tracker with a focus on military traffic turned out to be more about architecture than decoding.

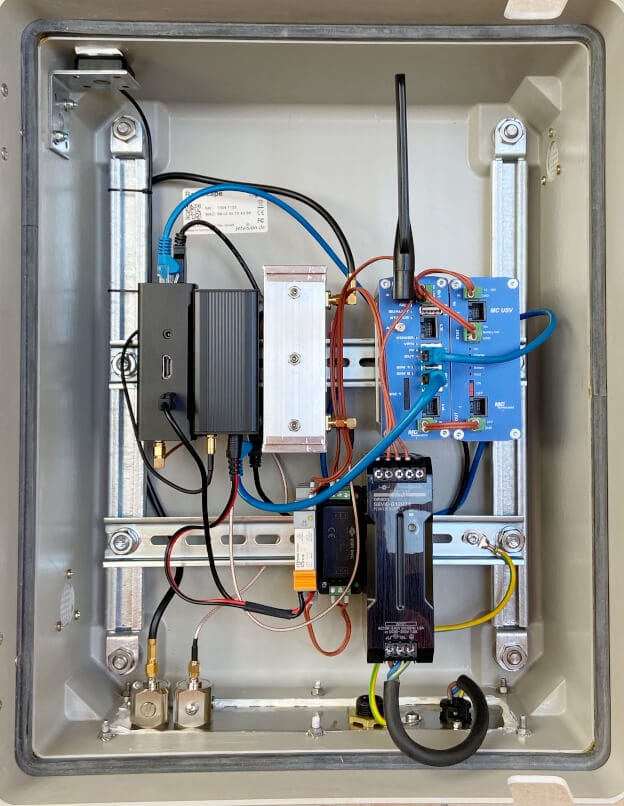

Living close to a major airport means the 1090 MHz spectrum is dense—hundreds of messages per second during peak hours. A full-featured app running on the same Raspberry Pi that holds the RTL-SDR dongle quickly becomes impractical. Even on a Pi 4 the combination of decoding, database writes, ML inference for anomaly detection, and serving a reactive frontend pushes CPU and I/O too hard for reliable 24/7 operation. Heat builds, SD card wear accelerates, and small glitches cascade into missed positions.

ADS-B is just a stream

Before diving into architecture, it helps to understand what the Raspberry Pi is actually doing when it receives ADS-B.

ADS-B (Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast) transmits on 1090 MHz using a pulse-position modulation scheme called PPM. Each message is 112 bits (extended squitter) or 56 bits (short squitter), preceded by an 8 µs preamble consisting of four pulses at specific intervals: 0, 1, 3.5, and 4.5 µs. The decoder looks for this preamble pattern to identify the start of a message.

The RTL-SDR dongle samples the 1090 MHz band at 2 MS/s (mega-samples per second). At this rate, each bit in the ADS-B message spans roughly 2 samples. The RTL2832U chip inside the dongle performs direct conversion: it mixes the RF signal down to baseband I/Q (in-phase and quadrature) and streams 8-bit samples over USB to the Pi.

The decoding pipeline works like this:

librtlsdrreads raw I/Q bytes from the USB interface in ~256KB chunks- Each I/Q pair is converted to magnitude:

√(I² + Q²). Readsb uses a lookup table for speed - A sliding window correlates against the known preamble pattern. When correlation exceeds threshold, a candidate message begins

- The decoder samples at bit centers (1 µs intervals) and applies a threshold to determine 0 or 1

- Each message includes a 24-bit CRC. Invalid CRCs are discarded (or corrected if single-bit errors)

- The Downlink Format (DF) field identifies message type—DF17 is ADS-B position, DF11 is all-call reply, DF4/5 are altitude replies

On a Raspberry Pi Zero 2 W, this pipeline consumes 40–60% CPU near a busy airport. The bottleneck is magnitude computation and preamble correlation—both are tight loops over millions of samples per second. Readsb optimizes this with NEON SIMD instructions on ARM, which is why it outperforms older dump1090 forks on Pi hardware.

The 1090 MHz antenna matters

Signal quality directly affects decode rate. I use a simple quarter-wave ground plane antenna: a 69mm vertical element (¼ wavelength at 1090 MHz) with four radials at 45° angles. This gives roughly 5 dBi gain toward the horizon where aircraft actually are. The RTL-SDR Blog V3 dongle includes a built-in LNA and 1090 MHz bandpass filter, which helps reject out-of-band interference from nearby cell towers.

Positioning the antenna outdoors or in a window with clear sky view is critical. ADS-B is line-of-sight; every wall or roof attenuates the signal. My setup places the Pi in a weatherproof enclosure on the roof with a 5m USB extension to the antenna.

Beast Protocol Forwarding

The Pi exposes Beast-format output on TCP port 30005. Beast is compact binary, roughly 20–25 bytes per message after framing, so forwarding over LAN costs almost nothing in bandwidth. A simple socat line in a systemd service handles the stream with automatic reconnection:

socat TCP-LISTEN:30005,reuseaddr,fork TCP:server-ip:30005

No polling, no JSON overhead, no reinvented protocol. If the link drops for a minute the server just waits; when it reconnects the stream resumes without state loss because each Beast message is self-contained.

Military tracking challenges

Military tracking is the interesting part. Many tactical aircraft either suppress ADS-B entirely, use it sporadically, or fly with blocked tail numbers. Near a busy international hub you still catch plenty via Mode S—all-calls replies give you the ICAO address even without position. The real gaps come from deliberate omission of position or from formations where only one plane squawks full data.

To close those gaps I pull from two external feeds. OpenSky Network provides multilateration (MLAT) positions for aircraft that are heard by enough community receivers but do not broadcast ADS-B themselves. Their API is rate-limited, so I cache aggressively and only query when my local feed sees a promising hex without recent position. ADS-B Exchange offers an unfiltered feed that includes many military transponders commercial aggregators block or sanitize. I subscribe to their websocket and merge messages when my local signal is weak or absent.

data fusion

Merging is where the trade-offs show up. Different sources have slightly different timing and coordinate precision. A naive union produces jittery tracks. Instead I implemented a simple fusion rule: prefer local ADS-B when available (lowest latency, highest trust), fall back to OpenSky MLAT if position age > 30 s, and use ADS-B Exchange as the last resort or for blocked tail enrichment. A short sliding window deduplicates by hex and timestamp to avoid double-plotting.

Lessons Learned

The hardest part was accepting that perfect coverage is impossible. Military operators design around exactly the kind of passive listening I do. Some flights never appear; others show only briefly. The system is good enough to catch most interesting movements in my area, and the split architecture keeps it running without babysitting. The Pi has been up for months now with zero manual intervention beyond power outages.

If I were starting over I would still choose readsb over alternatives and Beast over JSON for forwarding. The database split—time-series for positions, relational for enrichment—feels right; trying to force everything into one store creates query pain later.

The real lesson is in the humility of the architecture: offload what you can, accept partial visibility, and build fusion logic that degrades gracefully rather than pretending the data is complete. That mindset has carried over to other personal sensor projects since.